Watchet's Heritage - The Mineral Line

There are a good number of abandoned railways throughout Britain and in many cases they have become a great source for recreational walking and cycling. There is a section of the old West Somerset Mineral Railway that runs from Watchet to Washford, following the rich, fertile valley that crosses the old Pilgrim's Path near Kentsford Farm, (once the seat of the Wyndham family), the medieval route to Cleeve Abbey and St Marys Chapel at Blue Anchor.

For a good deal of this gentle walk, the Washford River runs adjacent to the path as it meanders its way to the sea. This much-loved route of about two miles has become a nature lover's delight and for much of the way, it is flanked by trees and dense undergrowth, a perfect environment for a diverse range of wildlife that includes the kingfisher and otter.

In a little over a hundred years, it has emerged not by design but by nature's whim. It is an unexpected and highly valued legacy of a lost industrial heritage, once so much part of West Somerset. In the nineteenth century, it was a very different place and any bird song would have been drowned out by the noisy clatter of the iron ore trucks on their journey to Watchet harbour and the waiting ships berthed at the wharf to take the ore to Ebbw Vale across the Severn Sea to Wales.

We can only imagine the excitement, no doubt tinged with an element of terror, as the first steam engines, belching smoke and clattering noisily over the iron rails, made their way through a countryside much more accustomed to the sedate progress of the horse and cart. The iron ore was completing a journey from the mines high on the Brendons, some 1300 feet above sea level and the most significant aspect of the industrial revolution to reach this sleepy part of Somerset.

The line was 11 miles in total and the first consignment of ore reached the harbour in 1857. In 1865, the line opened for passenger traffic, operating four trains a day with stations at Watchet, Washford and Roadwater, terminating at the incline at Combrowe. The stations have been beautifully captured in a series of photographs of the period. It is still possible to see evidence of the line today if you look carefully in converted buildings and other curiosities, although it is not possible to walk the entire length as much of the original line has been built over.

Although employing as many as 250 individuals at the height of its production, the initial expectations were never realised and by 1879 the writing was on the wall. Although mining continued with an interruption or two, by 1883 all mining ceased and all leases were surrendered. It staggered on with its passenger service but in 1898 it was finally closed and all rolling stock was either scrapped or returned to Ebbw Vale. It must have appeared a pretty dismal and depressing sight with buildings boarded up and grass growing through the rails as nature gradually began to reclaim the land.

Brendon Village, the once vibrant community with a school, chapels and its own shop all but disappeared as quickly as it had arrived and when the mines were closed in 1883, the miners dispersed to find employment in other parts of the country. There was however a bit of early recycling. The Anglican tin church, not much more than a corrugated iron hut that had opened for worship in 1860 and doubling up as the village schoolroom, fell silent. The Tin Tabernacle, as this building was known at the time, appears to have found a new lease of life at the Paper Mill in Watchet soon after 1883, as contemporary photographs illustrate. It was no doubt as well-attended by the mill workers as it had been by the miners because the mill hands were obliged to attend a service lasting half an hour before starting their shift. The Beulah Chapel however remains to this day and was saved thanks to the Reverend TC Jacob (the circuit minister) who called a meeting of local representatives to support his proposal of restoration. The contract for £139 was won by Messrs Sully and Son of Stogumber.

The terraces built in the 1850s and sixties became deserted and unlikely to find new occupants in such a remote location. In an admirable display of recycling, windows, tiles, etc were utilised in building elsewhere, notably in a row of cottages in West Street at Watchet, built in the late nineteenth century.

You might suppose that this brief flirtation with mines and railways had come to an ignominious end and was destined to be consigned to history, but you would be wrong. The great storm of 1900 had all but destroyed the harbour at Watchet, the community was devastated but, used to setbacks and made of stern stuff, the residents set about forming themselves into an Urban District Council, a necessary action in order to raise funds to rebuild the harbour. A second storm in 1903 caused further problems but eventually the work was completed and an air of optimism returned to the town. With this optimism came the forming of the Somerset Mining Syndicate as a group of local businessmen set about the reopening of the Brendon Hill mines. The incline was reopened and the Colton mine was the first to produce iron ore and, bearing in mind there are 80 individual mine shafts on the Brendons, they had plenty to choose from!

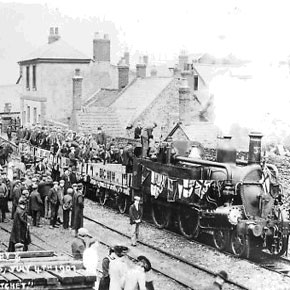

A new adit at Timwood included a tramway from Colton pit to the incline. The mines were opened and the line operational again and amongst much pomp and circumstance, the first passenger train left Watchet station on the 4th of July 1907. The optimism that had accompanied these beginnings was sadly never realised - the quality of the ore extracted just wasn't good enough. In an attempt to improve the iron ore by pressing it into blocks, the Briquetting Syndicate was formed and kilns built at Washford to rectify the problem. Sadly, this proved fruitless and both the Briquetting Syndicate and the Somerset Mining Syndicate went into liquidation in 1910. That was the end of mining on the Brendons. The rusting rails were removed in 1917 to help with the war effort. In 1924, an auction was held in Watchet of all the land and buildings, quite literally the end of the line.

The building in Market Street, originally the Engine Shed is now a garage and Indian Restaurant and is well preserved. From here the line crossed the road giving access to the East Quay to load the ore directly into the waiting ships. There were crossing gates that were operated manually on a daily basis. A piece of the line is preserved on the pier with an interpretation board giving a little information of the history. It is possible to distinguish the original station by the rather elongated building opposite and helpfully called Station House.

For further information about the town as a whole,

please visit the home page or click

Here

This page is provided by Watchet Conservation Society with the help of Watchet Chamber of Trade

and with funding from Somerset West & Taunton Council's High Street Emergency Fund.

Text and history provided by Nick Cotton